Overmountain Men

History

In the summer of 1780, the Southern American colonies – and hopes of independence – seemed at the mercy of an invading British army. Believing the Southern colonies mostly loyal, the Royal army planned to conquer the South and recruit Loyalist militia (local volunteer soldiers) to help British regulars and British Provincial troops defeat the Continental Army and the local Patriot militia.

When Charleston, South Carolina, surrendered May 12th, 1780, the British captured most of the Continental troops in the South. Additional large losses occurred later in the summer with Patriot defeats at Waxhaws, South Carolina, May 29th, and Camden, South Carolina, August 16th. Only Patriot militia remained to oppose a British move through North Carolina into Virginia, America’s largest colony. Victory for Royal troops and an end to talk of independence seemed near.

Lord Charles Cornwallis, the British commander, appointed Major Patrick Ferguson as Inspector of Militia for South Carolina to defeat the local militia and to recruit Loyalists. Ferguson’s opposition included men from South Carolina’s backwoods under Thomas Sumter, North Carolinians commanded by Charles McDowell, and Over mountain men from today’s Tennessee under Isaac Shelby.

Moving into North Carolina, Ferguson attempted to intimidate the western settlers, threatening to march into the mountains and “lay waste the country with fire and sword” if they did not lay down their arms and pledge allegiance to the King. The response was a furious army formed on the western frontier. Growing in numbers as they marched east, some 900 men gave chase to Ferguson, surrounding his army at Kings Mountain, South Carolina, and killing or capturing Ferguson’s entire command.

” . . . That Turn of the Tide of Success” –Thomas Jefferson

Ferguson’s defeat was a stunning blow to British fortunes. The strength of the Patriot militia was affirmed. The hoped for Loyalist support didn’t materialize. Cornwallis was forced to pull back from North Carolina, giving the Continental Army time to bring fresh regulars and new commanders south. On January 17,1781, Daniel Morgan, using Continentals and militia, defeated Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British army at Cowpens, South Carolina. That winter saw a running campaign between Cornwallis and the armies of Morgan and Nathanael Greene. Try as Cornwallis might, the Americans always seemed to cross the river to safety before Cornwallis could cut them off.

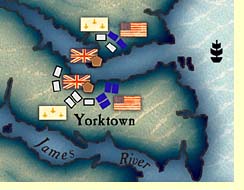

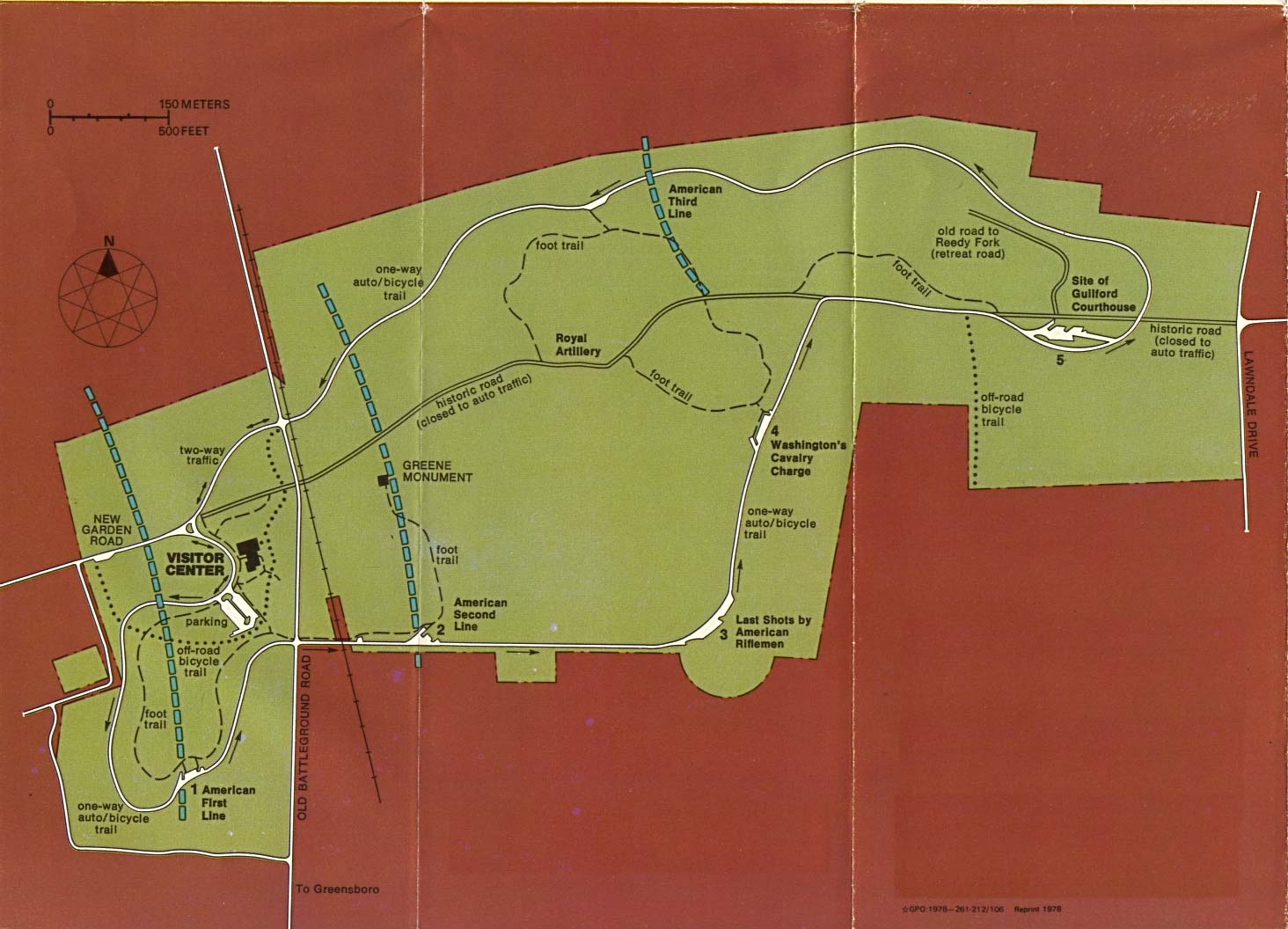

At Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, on March 15th, Greene finally turned to face Cornwallis. Greene’s army was driven from the battlefield, but Cornwallis suffered severe losses which he could not replace. Cornwallis pulled back to recuperate, finally moving his army north into Virginia without subduing North Carolina. In the fall of 1781, George Washington rushed his army south to join French reinforcements. When French warships fortuitously gained control of the Chesapeake Bay, Cornwallis was besieged and forced to surrender on October 19,1781, just over a year after Kings Mountain.

Kings Mountain was the beginning of the successful end to the Revolution, assuring independence for the United States of America. On an unimposing and obscure mountain, Americans fought Americans to determine their destiny. The citizen militia of the community, the predecessors of today’s National Guard and Reserves – like volunteer fire departments – organized to protect their community.

Men without formal training or recognized social standing – Ferguson called them mongrels – took hold of their destinies, just like the men who began the American War for Independence on April 19,1775, at Lexington and Concord. They relied upon their individual initiative, skills with the rifle, and courage to ensure the success of their cause.

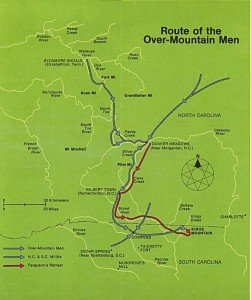

September 12, 1780, Charles McDowell ambushed part of Ferguson’s army at Cane Creek but was driven off and fled to Sycamore Shoals to await reinforcement by the Overmountain men.

September 25, 1780 Shelby, Sevier, Campbell mustered the militia of the Watauga and Holston Valleys at Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River (Elizabethton) to join Burke County militia under Charles McDowell. Fort Watauga is today reconstructed at the Tennessee historic area. In 1780, this was North Carolina, later Franklin (or Frankland), later Southwest Territory.

September 26, 1780, the army spent its first night at Shelving Rock, storing their powder out of the rain.

September 27, 1780, snow fell on Roan Mountain as the army crossed. Yellow Mountain Gap, at 4682 feet, is the highest point on the trail. Here two men deserted to warn Ferguson of the Patriot army.

September 30,1780, North Carolinians under Benjamin Cleveland, Joseph Winston, and William Lenoir joined the Overmountain men at the McDowell home at Quaker Meadows.

October 1 and 2, 1780, the army stopped to dry out and prepare for battle expected soon. Unpopular Charles McDowell was persuaded to step aside as commander. William Campbell, not from North Carolina, was chosen as a compromise replacement. McDowell rode to ask for a Continental officer to command.

October 3, 1780, the army camped beneath Marlin’s Knob beside Cane Creek. South Carolina Patriots under William Hill and Edward Lacey were camped nearby at Flint Hill (Cherry Mountain).

October 4, 1780, entering Gilbert Town, they found Ferguson had left, possibly headed towards Ninety Six in South Carolina.

October 5, 1780, reassured they, were following Ferguson, the army proceeded to the Green River, away from Kings Mountain. Small parties of Georgians under William Candler and North Carolinians under William Chronicle joined the Overmountain men. Early the next morning, Edward Lacey rode in with news they were headed away from Ferguson.

October 6, 1780, finally convinced Ferguson headed east toward Charlotte, the men with the best horses raced off to meet with Lacey and Hill’s South Carolinians.

The two groups united the evening of October 6th at Cowpens. Eating a hasty meal, the parties pushed on through a rainy night.

October 7, 1780, about 3:00 p.m. they found Ferguson’s Loyalist army on Kings Mountain. The two sides fiercely contested the wooded slopes until Ferguson was shot from his horse, killed with some 120 of his men. Only 40 Patriots fell.

October 7, 1780, at dawn the Patriot army successfully crossed the flooding Broad River at Cherokee Ford.

During the return, October 14, 1780, at Biggerstaff’s Old Fields (Bickerstaff’s or Red Chimneys) 30 Tories were tried. Nine were hanged, the others spared.

Many of the Patriot militia who fought at Kings Mountain returned to Cowpens, January 17, 1781, to help Daniel Morgan defeat another brash, young British commander, Banastre Tarleton.

At least five African-Americans are known to have served in the Patriot army at Kings Mountain.

People Involved

William Campbell

Leading the largest contingent, Virginian Campbell was chosen by his fellow colonels to command in Charles McDowell’s place. Campbell died in 1781, just before Yorktown.

Charles McDowell

A tireless campaigner in 1780, he stepped down from command rather than split the Patriot army.

Isaac Shelby

Later first governor of Kentucky, Shelby was a strong, forceful influence the summer of 1780. The morning of October 7th, he refused to stop and rest when the men tired after spending 36 hours on the march, vowing to follow Ferguson into Cornwallis’ lines, if necessary.

John Sevier

Later Tennessee’s first governor, John Sevier was the best known man west of the mountains and gave his personal guarantee to fund supplies for the militia army.

Mary Patton

This little-known Tennessee woman manufactured 500 pounds of powder purchased by William Cobb for the Overmountain men. Benjamin Cleveland The voice for independence in Wilkes and Surry Counties, Tories attempted to ambush Cleveland on his way to Quaker Meadows, wounding his brother instead.

Edward Lacey

Commanding South Carolina troops, Lacey rode through the stormy night of October 5th to intercept the Overmountain men at Green River and head them towards Kings Mountain.

Major Patrick Ferguson

Intelligent, brave, charming, inventive, headstrong, he fruitlessly advocated use of Patriot “Indian-style” warfare, yet he relied on the bayonet charge at Kings Mountain, allowing his army to be surrounded.

Abraham de Peyster

From New York, he served as Ferguson’s second in command. He lived in New Brunswick, Canada, after the Revolution.

Veazey Husband

A Loyalist from the Yadkin country near Cleveland, he was killed at Kings Mountain.

Patriot Troops at Kings Mountain

The Patriot commanders did not keep or report official rosters of their men engaged against Ferguson at Kings Mountain.

Dr. Lyman Draper’s “King’s Mountain and Its Heroes”, combined with pension applications filed by veterans and their survivors well after the battle, are the main sources of information about the army.

Dr. Bobby Moss in his “The Patriots at Kings Mountain” combines accounts from these two and other published sources to come up with brief biographies of the participants. (Dr. Moss compiled similar biographies on Ferguson’s men in his “The Loyalists at Kings Mountain”.)

Georgia:

Draper on page 214 says that Captain Edward Hampton met with Colonel Elijah Clarke as the Georgians retreated toward the Nolichucky after the aborted seige of Augusta. Major William Candler took a party of 30 Georgians to join with the Overmountain army against Ferguson. They joined up near Gilbert Town. Draper on page 227 indicates Candler joined Williams and entered the army at Cowpens with Lacey (Sumter’s men) and Williams.

North Carolina:

Draper on page 227 indicates about 90 men under McDowell (Burke), 110 men under Cleveland (Wilkes), and about 60 men under Winston (Surry) at Green River and Cowpens before the battle. In addition, he counts 50 men under Graham, Hambright, and Chronicle from Lincoln County joining up at Cowpens. Not counting the Watauga troops under Sevier and Shelby, North Carolina supplied 310 men out of the total Patriot force of 910 that Draper identifies. Adding the Tennesseans brings the North Carolina total to 550.

South Carolina:

Draper on page 227 indicates about 100 men under Lacey (Sumter’s men) and 30 under Williams joined the Patriot army at Cowpens before the battle. (This number subtracts the 30 Georgians under Candler who joined with Williams.) Draper estimates from this a total force of 910.

Tennessee:

Draper on page 227 indicates about 120 men under Sevier and another 120 men under Shelby at Green River and Cowpens before the battle. Draper estimates from this a total force of 910 in the Patriot army.

Virginia:

Draper on page 227 indicates about 200 under Campbell at Green River and Cowpens before the battle. Draper estimates from this a total force of 910 in the Patriot army.