Guilford Courthouse

(1781)

Despite the fact the Battle of Guilford Court House is a tactile draw, it remains a victory for the Americans as the British have been worn down so much that they will make a fateful retreat to Yorktown, Virginia.

The tide of the war in the South has turned with Daniel Morgans’ crushing defeat of Banaster Tarlton at the Battle of Cowpens. He reports back to Cornwallis who upon hearing the news is stunned. He does not hold Tarlton responsible, but blames it on the troops.

Cornwallis has been determined to crush General Nathaniel Greene and has pursued the General through the Carolina back country. Cornwallis has even made the unfortunate decision to modify his army as to make it more mobile and quicker. He has destroyed his baggage train, and forced his troops to scuttled their provisions. The British army is now forced to live off the land.

In the meantime Greene, full well knowing that Greene is on his trail, makes a race for the Dan River. Greene stops at Guilford Court House which will be the ground of the fateful battle.

On the 15th of March, Cornwallis sets his army in motion to cover the last 12 miles to Guilford Court House. He does not know the terrain, and has fewer than 1200 troops at his disposal. Cornwallis misguidedly believes that the best of the British army can overcome the odds which lay ahead.

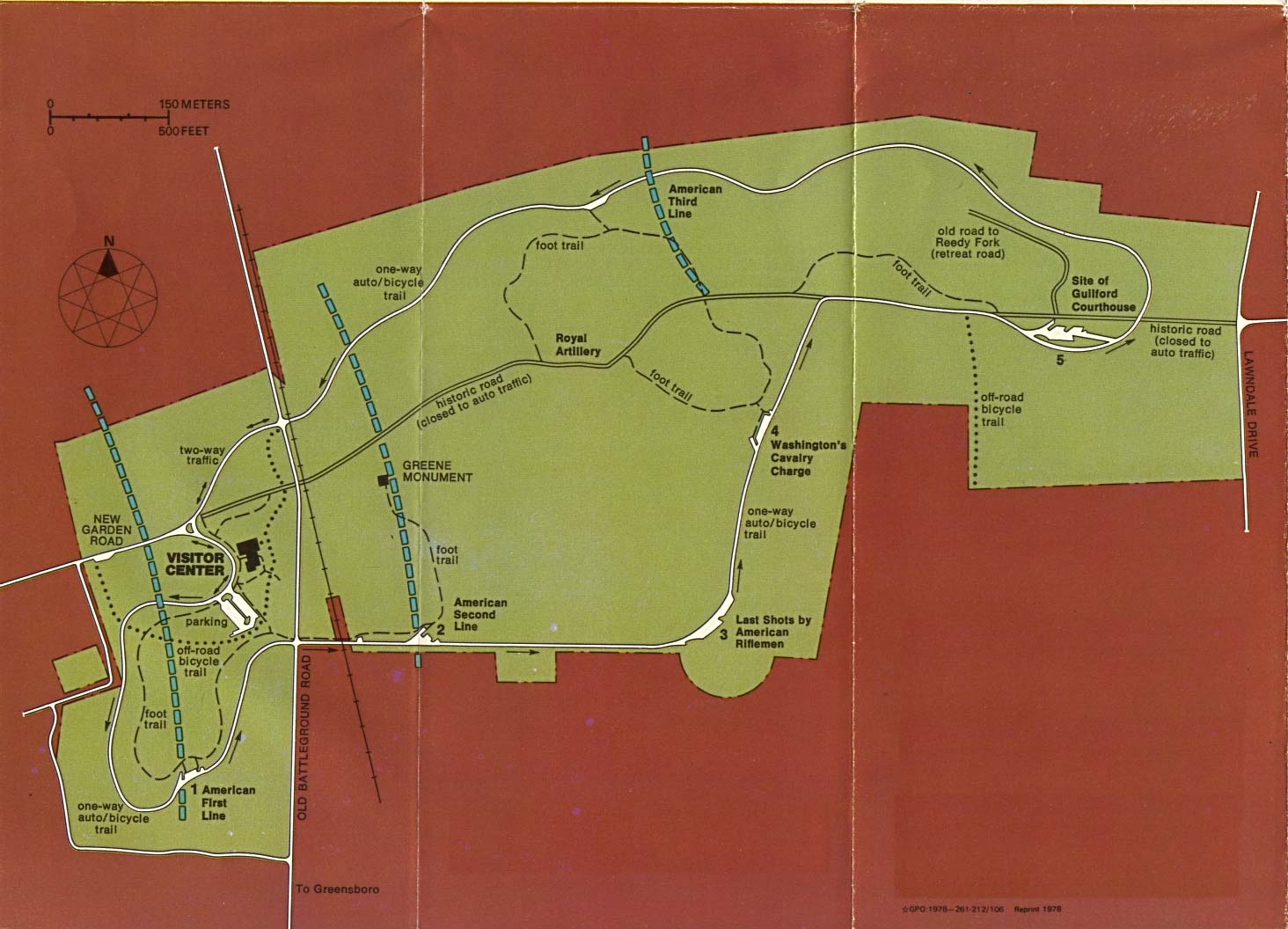

General Greene chose for his stand against Cornwallis a nondescript stretch of low rolling hills, broken here and there by moderately steep ravines. A forest of tall hardwoods, much of it with thick undergrowth, covered most of the ground. The main Hillsborough-Salisbury road, then the most important in North Carolina, ran east-west through the woods. Greene arrayed his troops astride the road, facing west, to block the British, marching along it toward them. His army of over 4500 outnumbered the enemy better than two to one. Sounds of a severe skirmish four miles east, between Campbell’s riflemen and the van of Cornwallis’ army, had alerted Greene and given him time to form his troops. The Americans were ready.

In front, at the western skirt of the woods, behind rail fences and looking out over cleared fields, was a north- south line of over 1000 North Carolina militiamen. One brigade was north of the road under a General Eaton and General Butler’s was south of it. Behind them in the woods, 300 yards east, were the Virginia militia, also around 1000 strong. Again the road was a dividing line. Robert Lawson’s brigade on the north was drawn mainly from Virginia’s southside counties: Pittsylvania, Prince Edward, Cumberland, Amelia, etc. Edward Stevens’ was composed in considerable part of men from the western Virginia ‘rifle counties’: Rockbridge, Augusta, Rockingham, and perhaps others. Their officers and many in the ranks were experienced soldiers who had fought in earlier campaigns, mostly against Indians. This brigade would be fighting south of the road where the ground was a little rougher and the woods thicker. It was their kind of country. As added encouragement, General Stevens put a line of sentinels in their rear with orders to shoot anybody who tried to run away.

A half-mile east of the Lawson’s brigade, near Guilford Courthouse and wholly on the north side of the road, Greene posted his line of 1500 Continental foot soldiers, one brigade from Virginia on the north or right flank, and another from Maryland, running southways on an arc bowed toward the west and reaching the road somewhat west of Guilford Courthouse. A series of open fields sloped down and away from the Continental front, westward into a narrow cleared valley. It was the best defensive position on the battlefield, offering high ground, forest cover to the immediate rear, and open fields of fire in front. Also, and by no means coincidentally, lying a few score yards to the rear of the Continental line and protected by it, was the army’s escape road. This led north from the courthouse to Speedwell Furnace on Troublesome Creek, halfway to the Dan crossings into Virginia.

There was a battery of four English- cast, six-pounder brass cannons, called ‘butterflies’, from the Virginia Regiment of Artillery. These were posted at the center of the North Carolina line and would fall back along the road as events proved necessary.

Finally, Greene had two somewhat misnamed ‘corps of observation’ for use in the harassment of Cornwallis’ flanks and the protection of his own. They numbered around 500 each. The one on the north consisted of William Washington’s regular Virginia cavalry, Robert Kirkwood’s company of Delaware continentals, and Colonel Charles Lynch’s 360 riflemen from Bedford County, Virginia. And there was a similar unit composed of the Virginia Legion of Light Horse Harry Lee, a regiment of cavalry with a company of Continental infantry, plus 350-400 riflemen under Colonel William Campbell, most of them from western Virginia counties and the rest from North Carolina. After their mid-morning fight at New Garden Meeting House, they were now formed in a west trending, wooded ravine which marked the southern limit of the cleared fields lying before the North Carolinians’ front line.

What did Greene hope to accomplish by these dispositions, and how closely did they conform to Dan Morgan’s letter of advice to him on how to fight Cornwallis? Two thirds of his best Virginia riflemen were placed on the flanks under their own ‘enterprising officers’ as Morgan had recommended. And, like Morgan at the Cowpens, Greene had posted his musket militias in the center and in front of his Continental line, with orders to get in a few good rounds and then withdraw. But Morgan had also warned him that the militias might not fight at all, in which case: …[Cornwallis] will beat you and perhaps cut your regulars to pieces , which will be losing all our hopes. And it is this thought which seems to have dominated his battle plan at Guilford.

Greene’s post was with his regulars a half mile through the woods to the rear of his militias. He could not control, support, or even observe them. But he was guarding and practically on his planned route of retreat, and no matter what the militias did or didn’t do, he could save his regulars by going back to Virginia. He might get beat but he was not going to preside over a disaster.

But if the militias did fight, what might be expected to happen? Cornwallis’ army would deploy in a line and run, or rather stumble, through a half-mile gauntlet in the forest, severely impeded, harassed, and deranged by trees and undergrowth and by frontal fire from the two lines of militia. And killing, enfilade fires would come from the corps of riflemen on both flanks, who were instructed to keep even with the British progress all the way back to the Continental line. There, the redcoats might be sufficiently exhausted and reduced in numbers, that Greene’s regulars could destroy them by close-in fire and bayonets in a general melee.

It was a good plan, in keeping with the Quaker General’s subtle approach to warfare. It offered reasonable guarantees against disaster, some chance of winning, and even better chances of doing severe damage to the British with his expendable militias and escaping with his regulars intact.. But it was only a plan. And marching up the road was the completely unsubtle Lord Charles Cornwallis with an army of veteran killers. The only plan he knew or cared to know was straight-up-the-middle, all-out fighting; victory or perish. He arrived in front of Greene’s carefully positioned North Carolina militia early in the afternoon of March 15th, 1781:

The advanced British units emerge from the woods to find a line of militia, in two lines. The first line is behind a log fence, the second behind a line of trees. Beyond the militia, are the battle tested Maryland and Delaware troops, and Washington and Lee’s dragoons on the flanks. Greene had entertained an action similar to Morgan’s at the battle of Cowpens, but distance is far greater here, and it would be impossible to coordinate the troops. Furthermore, Greene has no reserve element to throw into the fray.

Cornwallis is at an equal disadvantage. He does not know Greene’s strength, or his deployment of the troops.

The engagement begins with the flank elements of mounted infantry from Tarlton and American mounted infantry engaging each other. Cornwallis also has 3 light field guns at his disposal.

… I ordered Lieutenant Macleod to bring forward the guns .[two or three three-pounders, ‘grasshoppers’] and cannonade their center The attack was directed to be made in the following order:

On the right the regiment of Bose .[Hessians] and the 71st regiment .[Highlanders], led by Major-general Leslie and supported by the 1st battalion of guards; on the left, the 23rd .[Royal Welsh Fuzileers] and 33rd .[English foot] regiments, led by Lieutenant-colonel Webster, and supported by the grenadiers .[Guards company] and 2d battalion of guards, commanded by Brigadier-general O’Hara; the yagers .[Hessian light infantry company] and light infantry of the guards remained in the wood on the left of the guns, and the cavalry .[Tarleton’s legion] in the road, ready to act as circumstances might require. Our preparations being made, the action began at about half an hour past one in the afternoon; Major General Leslie, after being obliged, by the great extent of the enemy’s line, to bring up the 1st battalion of guards to the right of the regiment of Bose, soon defeated everything before him; Lieutenant Colonel Webster …was no less successful in his front .[left of the road]; when, on finding that the left of the 33rd was exposed to a heavy fire from the right wing of the enemy, he changed his front to the left, and, being supported by the yagers and light infantry of the guards, attacked and routed it, the grenadiers and 2d battalion of the guards moving forward to occupy the ground left vacant by the movement of Lieutenant-colonel Webster…

When Webster’s brigade on the left wheeled to face the terrible enfilade fire of Lynch’s Bedford riflemen, it was joined on its own left by the two reserve light infantry companies and, on its right, the Grenadier Guards and 2nd Guards battalion filled in the gap which had been opened to the immediate left, north, of the road. The advance of Leslie on the right, though he too had to commit the Regiment von Bose and his reserve battalion of guards against Campbell’s riflemen, was less troubled. Harry Lee, whose legion supported Campbell, recalled:

…When the enemy came within long shot, the American line, by order, began to fire. Undismayed, the British continued to advance , and having reached a proper distance, discharged their pieces and rent the air with shouts. To our infinite distress and mortification, the North Carolina militia took to flight, a few only of Eaton’s brigade excepted….All .[effort by officers to stop the flight] was vain; so thoroughly confounded were these unhappy men, that, throwing away arms, knapsacks, and even canteens, they rushed like a torrent headlong through the woods…

The characterization of Eaton’s resistance north of the road, as given by Lee, was taken from General Greene’s report rather than his own observation. By eyewitness accounts from that sector, the Carolinians did well enough, greeting the Welshmen with two or three well aimed rounds at reasonable range before they fled. But on the south, Butler’s brigade, by most credible accounts, broke and ran, as Lee says, without doing the Highlanders any harm. A lone exception was the company of a Captain Forbis, who refused to run away but joined with Campbell’s riflemen. These with the aid of Lee’s legion infantry brought sufficient fire on Leslie to force him to commit his reserve.

On the American right, north, Lawson’s brigade of Virginia militia put up a good, overall fight at the second line. Some companies ran away early. Others fired their requisite rounds before retreating. Still others refused to give ground to the charging British and fought from pockets of underbrush for a time after they had been bypassed. The flanking corps of Lynch and Washington, made another strong stand at the second line.

South of the road, the action at the second line was much more complicated and prolonged. Colonel McDowell’s Rockbridge battalion began its long fight at the extreme south end of the General Stevens’ line. In Private Sam Houston’s diary account, he refers to Eaton’s men when he says ‘Butler’s’, to Campbell’s flank corps of riflemen, which had three companies from Augusta County, when he says ‘the Augusta men and some of Campbell’s’, and to the 71st Highlanders when he speaks of the British. He was unaware of any North Carolinians to his front and, as they put up so little resistance, he may have mistaken the sound of their fire for that of a picket line:

Thursday 15th–Was rainy in the morning. We often paraded, and about ten o’clock, lying about our fires, we heard our light infantry and cavalry, who were down near the English lines, begin firing with the enemy. Then we immediately fell into our ranks, and our brigades marched out, at which time the firing was ceased. Col. McDowell’s battallion of Gen. Stephens’ brigade was ordered on the left wing. When we marched near the ground we charged our guns. Presently our brigade major came, ordering to take trees as we pleased. The men run to choose their trees, but with difficulty, many crowding to one, and some far behind others. But we moved by order of our officers, and stood in suspense. Presently the Augusta men, and some of Col Campbell’s fell in at right angles to us. Our whole line was composed of Stephens’ brigade on the left, Lawson’s in the centre, and Butler’s, of N. C., on the right. Some distance behind were formed the regulars. Col. Washington’s light horse were to flank on the right, and Lee on the left. Standing in readiness, we heard the pickets fire; shortly the English fired a cannon, which was answered; and so on alternately till the small armed troops came nigh; and then close firing began near the centre, but rather towards the right, and soon spread along the line. Our brigade major, Mr. Williams, fled. Presently came two men to us and informed us the British fled. Soon the enemy appeared to us; we fired on their flank, and that brought down many of them; at which time Capt.Tedford was killed. We pursued them about forty poles, to the top of a hill, where they stood, and we retreated from them back to where we formed. Here we repulsed them again; and they a second time made us retreat back to our first ground..

Houston is thought to have been in Tedford’s company. Andrew Wiley, 51 years later, recalling this series of attacks and counterattacks in his pension application, speaks from the slightly different perspective of David Cloyd’s company, also of the Rockbridge battalion. There are two versions of this account, one somewhat garbled and a second, less confusing, pasted over the first. I have used brackets here to insert interesting information from the first which was omitted by the interviewer from the second:

This applicant states that…at the outset of the action, the Carolina forces .[,who were formed into a line extending from where the cannon were stationed to the riflemen on the left wing,] broke and ran—that the Riflemen to which this applicant belonged were stationed upon the left wing—that when the Carolina line retreated, the British forces came down upon a ridge between the Riflemen on the left wing and a company .[formed on the rear of the left wing and] commanded by Col. Campbell of Rockbridge Cty. (then Augusta) who, as this applicant believes, brought on the action, and were swept off by the Virginia Riflemen, but formed again and again until finally they came down upon the ridge in columns of 12 and 16 men in depth .[but were cut off by applicant’s company] and were compelled to ground their arms…

By ‘brought on the action’ Wiley means that Campbell’s men had fought in an earlier skirmish, the same heard by Houston. The contingent of Highlanders, by Wiley’s account, resorted to a column assault tactic, rarely used in that age, to penetrate the angle between McDowell’s and Campbell’s riflemen. Its survivors were made prisoners. Houston didn’t learn of this capture til next day. Before it occurred, his company and Captain John Paxton’s, the two now led by Major Alex Stuart, became separated from the rest of the Rockbridge battalion under repeated assaults by the Scots and and their own efforts at counterattack. Henceforth they would fight a different battle, further south, in the same sector of the woods as Campbell’s men. The thread of their story will be picked up later.

General Stevens, after being painfully wounded in the thigh, ordered his brigade to retire to the third line. Colonel McDowell, with the remaining Rockbridge companies of Cloyd and, probably, Gilmore, retreated with them. The general was of notable corpulence, but was somehow carried by his men from the woods to Guilford Courthouse, and ultimately, all the way back to Troublesome Creek.

The British line up and advance on the center of the militia behind the fence. The militia let loose a volley than halts the British advance. The American line, then runs for the rear, running off the field. The British then concentrate their attacks on the flanks, and then prepare to move against the second line of the militia. The second line puts up a fierce fight, but is eventually driven back. The flanks of the Americans also start to give way. The British reemphasize their attack against the center only to find the battle hardened Maryland troops waiting. The Americans deliver a withering fire and follow up with a bayonet charge.

The British reserve troops come forward, and renew the advance. A regiment of untested American troops turn and run, leaving the British to advance on the defensive lines.

Meanwhile, the flank corps of Lynch and Washington had retreated to the third, the Continental line. The riflemen formed on the right of the Virginia brigade, and Washington, apparently learning that Lee’s legion had not yet arrived, rode with his troopers to the other end of the line and occupied a low hill just south of the road, so as to give flank protection to the Marylanders.

Then came Colonel James Webster with the 33rd Foot, the Guards Light Infantry, and the Jaegers, who had already had two sharp fights with Lynch and Washington, but now faced the center of the Continental line across the cleared vale, well north of the road. Hawes’ Virginians were to his left and Gunby’s 1st Maryland Regiment on his right. Webster promptly attacked. But the luck which had guided him across Reedy Fork under the guns of Campbell’s sharpshooters and in the charges which he had led against Lynch, now left him. When he and his men came within thirty yards or so of the Americans, they were met by a massive volley of musket fire from both regiments. The Colonel was one of those who fell. His kneecap was shattered, a wound which was immediately painful and disabling and would ultimately kill him. He was helped back across the ravine, where his men quickly retreated, and found a good observation point from which he could watch developments along the whole line. On the other side, Colonel Gunby was also disabled when his wounded horse fell on him. Command of the 1st Maryland was soon passed to John Eager Howard, who had capably commanded Morgan’s line of Continentals and Virginia riflemen at the Cowpens.

Before Webster’s action was concluded the 2nd Guards Battalion and Grenadier Guards arrived on the road opposite the 2nd Maryland Regiment which was posted at the south end of the Continental line. Brigadier O’Hara was still with the Guards, but Lieutenant Colonel James Stuart had assumed active command because of O’Hara’s wounds. Stuart ordered an immediate charge.

The 2nd Maryland, a recently regularized militia unit led by Colonel Benjamin Ford, was the least experienced and most questionably officered of Greene’s Continental regiments. It had been placed at this post of most obvious danger and sensitivity by Otho Williams, brigade commander of the Maryland Line. It was supported by two six pounders. These Continentals fired a half-hearted, ineffective volley at the advancing Guardsmen, dropped their muskets and ran away. None of Greene’s much defamed militia had ever behaved worse or with more damaging effect. The jubilant lobsterbacks now rushed by the abandoned guns, poured around a thickety little woods, which had separated the two Maryland regiments, and headed for the rear of the Continental line.

Several key commanders realized what was happening at about the same time and took various actions. Colonel Otho Williams, commander of the Maryland Brigade, had just watched the repulse of Webster and now rode over to see how his other regiment was doing. When he saw, what he did was send aides galloping to Greene and Howard with the bad news. What he said, surely something choice, is unrecorded. Colonel Howard, after quickly consulting the fallen Gunby, faced his 1st Maryland Line about and wheeled them into position to block the British from the army’s rear. Colonel Webster, seeing an opportunity as the 1st Maryland’s move exposed Hawes’ flank, ordered his bleeding 33rd and their light infantry support back across the vale to assault the Virginians. But Kirkwood’s Delaware company, and, possibly, some of Stevens’ militia brigade came up beside Hawes. General Nathanael Greene gave orders to prepare for a general retreat. But things were happening much too fast for his orders to affect events already in progress.

Colonel William Washington was watching from his hilltop just south of the road. He gathered up his great roly-poly frame, swung up onto his horse, drew his saber, and ordered his cavalry to charge the Guardsmen. He led the van himself, as always. Riding with the fierce, moonfaced leader of horsemen on this day was the Virginia giant, Private Peter Francisco of the Prince Edward County militia. He was six foot eight and supposed to be the strongest man in the Commonwealth. He swung a specially forged five-foot broadsword. They thundered down the slope on their great warmblood horses, crossed the road, jumped the ditch beside it, and hit the startled Guards at a gallop. They cut and trampled their way through, shattering the ranked formations, then turned and overrode them again, going the other way. Francisco is most frequently credited with eleven kills in the action, but he only remembered four in his own pension application. One redcoat pinned the giant’s thigh to his horse’s flank with a bayonet. By the legend, he leaned over and, with free hand, helped the Guardsman withdraw the weapon before, with sword, he cleft him, helm and skull, down to the collar bone. Now Howard’s 1st Marylanders fell on the broken British, closing with them after only one point-blank volley. Captain John Smith, after cutting down a Guardsman, was attacked by James Stuart, Guards’ Colonel. Stuart lunged with his short sword, missed, stumbled over the fallen soldier, and was killed by Smith with a backhand slash. Then the colonel’s batman came at Smith but was killed by another Marylander. Smith cut down one more guardsman before he was shot in the back of the head. Some of Washington’s riders lingered with mounted senior infantry officers on the periphery of the fight, slashing at redcoats who tried to break out.

The swirling mass of men and horses, bayonets and sabers, moved westward, past the guns again and toward the British side of the vale, propelled mainly by desire of the surviving Guardsmen to escape the apocalyptic nightmare that enveloped them. Among some newly arrived British on the west side was Cornwallis. One of his proudest units was broken and being slaughtered before his eyes. Fearing the spectacle might dispirit others, he put a quick end to the Guards’ agony. His artillery was up and he ordered Lieutenant Macleod to fire on the melee, friend and foe alike. This was done. Washington and Howard soon pulled their men back to safety, Smith’s men carrying their fallen Captain. To their surprise and enjoyment, he soon revived. A pathetic remnant of the Guards fled to the British side of the ravine. No officers came back with them, carried or otherwise.

The twice wounded Guards commander, Brigadier O’Hara, was lying by the British guns as they blasted his soldiers with grapeshot. His protests of the bombardment to Cornwallis and Macleod, if heard at all by them, were not obeyed. Now he reassumed command of the officerless survivors long enough to post them as replacements to the much depleted 23rd Welsh Fuzileers and 71st Highlanders, just coming up. Webster’s second assault had turned into a vicious seesaw fight with the Virginians and Delawares for another section of American cannons stationed there. Other preparations were made by their surviving officers to get the terribly battered British collected for a final assault on the Continental line. They weren’t necessary. If General Greene found reasons, in the clearing of his rear and the destruction of the Guards, to reconsider his decision to retreat, they weren’t strong enough to change his mind.

Cornwallis observing the battle sees mass confusion, and orders his artillery to fire on the entire mass, knowing that it will kill his troops as well. As the British prepare to advance, Greene retreats in good order leaving the field to Cornwallis. The terrible toll to the British is some 532 losses. The Americans however have suffered only 78 dead and 183 wounded. The British army is so worn down from this battle that it limps back to Wilmington N.C., unable to maintain a presence in the Carolinas.

The Earl Cornwallis, in his report to Lord Germaine two days later, embellished the events just described in such a way as to make it appear that the British pushed Greene off the field by main force. This was made easy for him because Greene abandoned his four cannons, unspiked, and over 200 rounds of ammunition with powder. But Greene’s retreat, by American reports, simply went as planned. His guns were left, he reported, for lack of horses to pull them. Why the pre-charged ammunition and powder were not blown or the wagons, limbers, and carriages not destroyed, is unknown. Here is Macleod’s report:

Return of ordnance, ammunition and arms,

taken at the battle of Guildford, March 15,1781

BRASS ORDNANCE

MOUNTED on travelling carriages , with limbers and boxes complete, 4 six-pounders. Shot, round, fixed with powder, 160 six-pounders; Case, fixed with ditto, 50 six pounders; 2 ammunition wagons; …

J. Macleod, Lieut…

Perhaps Cornwallis’ distorted report reflects a self-deception, an inability to believe that a General of Greene’s stature, ability and undoubted personal courage would, with five or six intact regiments, voluntarily abandon the battlefield, his wounded, and such a prize of artillery to an army as depleted, exhausted, and bloody as his own. And, though Greene almost certainly didn’t know it, he left a battle that wasn’t yet over.

The British cavalry leader Tarleton picks up the story: …Earl Cornwallis did not think it advisable for the British cavalry to charge the enemy, who were retreating in good order, but directed Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton to proceed with a squadron of dragoons to the assistance of Major-general Leslie on the right, where, by the constant fire which was yet maintained, the affair seemed not to be determined. The right wing… had a kind of separate action after the front line of the Americans gave way, and was now engaged with several bodies of militia and riflemen above a mile distant from the center of the British army. The 1st Battalion of the guards, commanded by Lieutenant-colonel Norton, and the regiment of Bose, under Major DuBuy, had their share of the difficulties of the day…

And according to other British reports of these ‘difficulties’ the ‘excessive thickness of the woods’ made their bayonets ‘of little use’ and enabled the enemy riflemen to ‘make frequent stands’ so that they suffered losses and delays while ‘warmly engaged on front flank and rear’. At one time the 1st Guards Battalion was ‘completely broken’ with the loss of most of its officers and had to be withdrawn from the action. Lee, by his report, thought the Guards were headed for the third line. He sent his cavalry to the Courthouse and, with his Legion infantry and a company of Campbell’s riflemen, got into the rear of the Guards and attacked them. The assault threw them back on the Hessians who were already being forced toward the Guards by Campbell’s riflemen. Lee now thought that Campbell’s men were more than a match for the surviving British and Hessians in their part of the woods. He hurried on back to the Courthouse. But Greene, meantime, had already begun his retreat. So the only serious result of Lee’s moves was that Campbell’s men were left without cavalry support as Tarleton’s dragoons rode through the woods toward the sound of their gunfire.

Tarleton says in his account that he rescued several groups of Hessian and British prisoners being held under light guard by riflemen in the woods. When he finally reached the survivors of the Regiment von Bose and the Guards, he says they were at the base of a rise of ground, held by a considerable force of riflemen. While the Hessians fixed their attention with a demonstration on their front, Tarleton rode in on their flank. Rockbridge Private Houston’s dairy also records this final action of the battle:

…we were deceived by a reinforcement of Hessians, whom we took for our own, and cried to them to see if they were our friends, and shouted Liberty! Liberty! and advanced up till they let off some guns; then we fired sharply on them and made them retreat a little. But presently the light horse came on us, and not being defended by our own light horse, nor reinforced –though firing was long ceased in all other parts, we were obliged to run, and many were sore chased and some cut down. We lost our major and one captain then, the battle lasting two hours and twenty-five minutes. We all scattered, and some of our party and Campbell’s and Moffitt’s collected together, and with Capt. Moffitt and Major Pope, we marched for headquarters, and marched across till we, about dark, came to the road we marched up from Reedy Creek to Guilford the day before, and crossing the creek we marched near four miles, and our wounded, Lusk, Allison, and in particular Jas. Mather, who was bad cut, were so sick we stopped, and all being almost wearied out, we marched half a mile, and encamped, where, through darkness and rain, and want of provisions we were in distress. Some parched a little corn. We stretched blankets to shelter some of us from the rain. Our retreat was fourteen miles.

The Regiment von Bose wore blue coats, similar to those of the Continental foot. ‘Moffitt’ is Colonel George Moffett who commanded the Augusta contingent of Campbell’s men. It was Major Alex Stuart that Houston says was lost, caught in a little clearing by Tarleton’s dragoons. They made the Major take off his boots and pants, stand there in epauletted coat and cocked hat only, while they beat the surrounding bushes for his riflemen. He was taken prisoner unhurt, and exchanged after a few months. In James Tate’s hard luck company from south Augusta, two who were chased were the Steeles, Samuel and David. Sam shot one dragoon during the rout, but was later captured by two of them before he could reload. When they commanded him to hand over his rifle, he just kept repeating: ‘O I couldn’t do that. I can’t do that.’ They let him keep it and a little later, while their attention was directed elsewhere, he loaded the weapon. And when they looked at him again, he brandished it at them. They fled. David was sabered about the head, his skull splintered. He was left for dead in the woods, but eventually revived and returned hom where the splinters were removed and a silver plate inserted. Both men lived into old age.

Also lost in the chase, from the Rockbridge Battalion, was Captain John Paxton, with a badly wounded foot which never completely healed. Presumably he lay in the woods overnight without help in cold downpour which began that evening. So did all the American wounded. The British had not even enough men left on their feet to tend all their own until next day. They lay down exhausted, without tents or rations, on bloody, rainsoaked Guilford battlefield. They slept amid hundreds of unburied dead, the cries and moans of hundreds more mangled and dying.

Sam Houston continues: Friday, 16th–As soon as day appeared (being wet) we decamped, and marched through the rain to Speedwell furnace, where Green had retreated from Guilfordtown, where the battle was fought, sixteen miles distant; there we met many of our company with great joy, in particular Colonel M’Dowell; where we learned that we lost four pieces of cannon after having retaken them, also the 71st regiment we had captured. After visiting the tents we eat and hung about in the tents and rain, when frequently we were rejoiced by men coming in we had given out for lost. In the evening we struck tents and encamped on the left, when the orders were read to draw provisions and ammunition, which order struck a panic in the minds of many. Our march five miles.

Soldiers’ superstitions, old as war: dread of being blown up by their own heavy weapons, lost to the enemy; of being killed by enemy soldiers they had already beat and captured, but let escape. But there wasn’t any need for panic. Greene, still wary of the British, would not go back and confront them. And Cornwallis, soon realizing that his shattered, hungry army was in no condition to fight again, simply declared the battle a victory, which was true. Then, less than three days after he came to Guilford, leaving both his own and the American wounded behind, he began a rapid retreat march to his coastal base at Wilmington, 180 miles south. Greene, declaring the campaign a victory, also true, trailed at a safe distance two days later.

On the 19th, a day before Greene began his pursuit, Charles Magill, Jefferson’s liason officer, wrote his Governor: …I am sorry to inform your Excellency that a number of the Virginia Militia have sully’d the Laurels reap’d in the Action by making one frivolous pretense and another to return home. A number have left the Army very precipitately. The best Men from Augusta and Rockbridge have been foremost on this occasion…

According to Sam Houston’s diary, many of the men had lost their blankets and coats during the fight. It was cool and rainy in the morning, warm and sunny most of the day, a cold forty-hour rain commencing in the evening. During the fight, coats would have been in the knapsacks, blankets rolled and hung from the shoulder. When being chased by Tarleton’s cavalry, packs would be the first thing a man might drop, assuming he was a good enough soldier to hold onto his rifle and ammunition. A cold forty-hour rain. Of course all this would sound like ‘frivolous pretense to a noncombatant Major at Greene’s headquarters. He hadn’t been chased. He had his warm clothes, even his pen and ink. He wasn’t shivering so hard he couldn’t write the elegant words that he wrote. In any case, by the time Greene decided to follow the British, the Rockbridge and Augusta riflemen had gone home to the Valley of Virginia.