Battle of Yorktown — The War's End

September 1781 – October 19, 1781

MIRACULOUS CONVERGENCE

"The first necessity [of the Yorktown campaign] was to arrange the meeting of French naval and American land forces on the Virginia coast at a specified time and place. The junction in Virginia had to be coordinated by two different national commands separated across an ocean without benefit of telephone, telegraph or wireless. That this was carried out without a fault seems accountable only by a series of miracles."

Scholar Barbara Tuchman in The First Salute

Moving an army in 18th century America was no easy task. Bridges were nearly non-existent; roads were trails; forage was always inadequate to the needs of thousands of men and animals.

On August 14, 1781, Washington and the French general Rochambeau received word from Comte de Grasse, the admiral of the French fleet, that he would be arriving off the coast of Virginia in mid-September. De Grasse would remain in the Chesapeake area for a month, until the expected seasonal heavy weather forced him south again.

Here was an opportunity to trap Cornwallis in Virginia, but to do so meant that not one, but two armies—one speaking English, one French—would have to travel 500 miles over local roads in a coordinated assault with a navy that was, at the time de Grasse's letter arrived, sailing somewhere in the Atlantic.

To further complicate matters, the American and French armies would have to leave their encampments in New York in the face of the large British army stationed there. If a whiff of their intentions wafted toward British lines, the British would certainly engage the allied armies.

They broke camp on August 19.

A guard of American militia and Continental regulars was left in New York to cover the Hudson River crossing of the 7,000 French and American troops who were heading south. The crossing was made without incident and the joined armies headed south at a rate of 15 miles a day.

On September 1, they'd reach Philadelphia, 130 miles down the road.

On September 2, British General Henry Clinton in New York learned that Washington and Rochambeau had slipped away and had just passed through Philadelphia, heading toward Cornwallis. He sent word to Virginia that the allies were coming.

On September 5, Washington discovered that de Grasse had arrived early in the Chesapeake with 28 ships and 3,000 troops. A British fleet was also cruising toward the bay.

An advanced force of the Continental Army reached Baltimore on September 12.

On September 16, Washington learned that, after an initial skirmish, the powerful French fleet had intimidated the British fleet away from the Chesapeake. The bay was in French hands.

"On September 28," Barbara Tuchman writes, "the clink of bridles and the rhythmic clomp of horses' hooves and tramp of marching men were heard in the British camp in Yorktown, announcing the approach of the enemy army from Williamsburg."

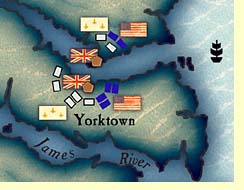

Yorktown was surrounded. In 3 weeks time, Cornwallis would surrender and the Revolutionary War would be all but over.

The battle of Yorktown began late in September 1781. The British General sent pleas for troop reinforcements and even considered ferrying his men across the river to safety. The French and Americans began a long bombardment, with the French artillery proving highly accurate.

No reinforcements, the continuous bombardment by French and Americans, and a loss of two key redoubts or hilltop fortifications to a night attack led by Washington's aide de-Camp, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton, led Cornwallis to see there was little hope left for his army. He surrenderd to Washington on October 19, 1781. Although is was not yet clear, the war was as good as over.